Biden Got One Big Thing Wrong On the Economy, and One Big Thing Right

Democrats didn’t pass the sort of policies that voters remember and respond to. But, despite inflation, they’ve managed the macroeconomy well. And they’ll probably be rewarded for it.

Here’s a question that’s bedeviling the commentariat: Why aren’t Americans giving Biden and the Democrats credit for a great economy?

Unemployment is currently 3.5 percent, which is as low as it ever got during Donald Trump’s presidency—and lower than it’s been since the late 1960s. The prime-age employment rate is now a little higher than it ever was under Trump, and well on its way to reaching an all-time high. Inflation has slowed considerably. Economic growth is still bouncing along at a respectable clip, defying widespread expectations of a recession.

Yet, when voters are asked to rank Biden on the economy specifically, his numbers are in the tank. A mere 32 percent approve of the job he’s doing, while 67 percent disapprove. Trump’s approval rating, when the economy was showing very similar headline numbers, was almost twice as high. A recent New York Times poll found that if Biden and Trump had a rematch tomorrow, they’d be in a dead tie. And the Democratic Party is panicking that they’ve lost voters on the economy.

Some leftwing critics point to the long-term problems of American capitalism to explain Biden’s conundrum: low unemployment or not, poverty and inequality remain widespread, and we still fail to make crucial needs like health care, education, and housing universal and affordable. All of which is true! But that’s why the comparison to Trump is helpful: all those long-term failures were present during his administration too. Yet they didn’t drag his numbers down.

So what gives?

One conclusion is that voters are detached from reality—whether because of cognitive biases built into human nature, reporting failures by the mainstream media, or the hypnotic power of rightwing propaganda outlets. There’s a very similar story progressives often tell about Republican voters specifically: that they’re completely indifferent to any material difference Democrats may make in their lives. The new version just extends the exasperation to the entire voting populace.

I find neither particularly compelling. Both sentiments tend to betray a self-satisfied elitism, not to mention a vague contempt for democracy’s very ability to function.

Generally speaking, if your data is saying the economy is good, and voters are telling you it’s not, you should assume your data is missing something. More specifically, if you want to understand how politicians—and in particular presidents and their parties—get credit for good economic outcomes, I’d say you need to look at two questions.

The first is, have there been specific policies or actions taken that earn voters’ goodwill? Think of Franklin Roosevelt passing Social Security or a bunch of New Deal jobs programs. Those policies made big, immediate, lasting differences in people’s lives, and voters remembered that Roosevelt and the Democrats did that.

The second question is good management of the macroeconomy. This is more of a general environmental condition that voters feel good about, rather than a specific act for which credit is given. Nonetheless, it’s usually the case that good economic conditions result in rising approval for the person (and party) that occupies the White House.

I think the basic story here is that Democrats blew it on the first question. But they did do pretty well on the second question. It’s just their success hasn’t become tangible to most voters yet, for reasons that are actually fairly mundane and obvious once you poke around under the hood. However, with a little luck, that should turn around before 2024.

Helping Americans Isn’t Enough; They Have to See You Do It

A branch of political science I think everyone should read—elected representatives especially—is the literature on “policy feedback.” In a nutshell, voters not only affect policy, but policy affects voters. The right government program can turn a random assortment of individuals into a coherent block of voters, with shared goals and a shared identity, and a shared incentive to reward the politicians and party that helped them.

Social Security is the quintessential example here. It didn’t happen because seniors organized and demanded it; President Roosevelt and the Democrats passed it for a host of other historical reasons. Instead, seniors organized into a powerful voting block in response to Social Security’s existence and the benefits it provided. And then seniors’ engagement and loyalty could be harnessed to power other political goals.

The policy feedback literature deals with, well, that feedback loop. Most importantly, it identifies several specific characteristics a policy needs to generate that voter feedback. Not just any policy will do the trick. There are plenty of policies that are good ideas, that make the economy better, that produce real material benefits for voters, but not in the specific ways voters can recognize and respond to.

President Biden and the Democrats have passed a lot of stuff. And I suspect a lot of people look at all that and think, “Holy shit, look at all the economic aid Biden has given voters! It’s absolutely crazy that his job approval on the economy is so low!” But if you look at the policy characteristics that best generate feedback from voters, it’s very obvious that the stuff Biden passed rarely matched the criteria:

Visibility and traceability of benefits. For a policy to create feedback, voters need to be able to easily see the aid they’re getting, and be able to see where it came from. Social Security benefits and the direct checks in the COVID-19 aid packages are examples of this done well.1 Tax credits, on the other hand, are a great example of this done poorly: they’re administered through the tax code, which is complex and opaque and a hassle. Indeed, tax credits are infamous for how often Americans fail to realize they’re benefiting from them. Outside of the direct checks, a lot of the aid in Biden’s American Rescue Plan was expansions of existing tax credits. As for the Inflation Reduction Act, it’s also mostly tax credits to households and businesses, and most of its spending hasn’t even gone out the door yet.

The proximity and concentration of beneficiaries. Programs that benefit a large number of people, who can recognize each other as a group with shared interests, are more likely to generate feedback. Thus, universal programs are much better than means-tested and targeted programs, as the latter benefit smaller populations that are more scattered and diffuse. There’s a reason Biden’s direct COVID-19 checks, which came close to being universal, were such a big focus of Democrats’ campaigning. But expanding the generosity of targeted programs like SNAP, TANF, and even unemployment insurance—all big parts of the American Rescue Plan—won’t get you nearly as much juice in terms of political credit.

Duration of benefits. This should be fairly obvious, but programs that last a long time are much more likely to generate feedback than programs that are short. This was a big downfall of the entire American Rescue Plan: the direct checks only happened once, and pretty much every other form of aid in the COVID-era programs has already expired.

How the program is administered. The experience of interacting with a policy can send a very clear signal to Americans about whether or not they’re valued. Social Security is experienced as a right and an entitlement—a clear sign that you’re a valued member of the national community, and we care about you. People will be grateful for that and respond accordingly. But if you’ve ever been on SNAP or TANF or unemployment insurance, to name a few, the experience is very different. Those programs are basically designed to make their beneficiaries feel guilty for receiving them. You’re required to constantly jump through tons of hoops to prove you’re “worthy.”

Many Americans barely remember the aid from the American Rescue Plan, nor are they aware of the genuinely big moves the Inflation Reduction Act made toward combating climate change. But this shouldn’t surprise anyone. It wasn’t a failure of messaging, and it wasn’t because people are addled by culture-war folderol. Those bills simply weren’t designed to encourage the policy feedback loop.

Assuming Democrats ever get another bite at the apple, that’s the lesson I’d love for them to take away. Voter goodwill doesn’t arise automatically; there’s a science to husbanding it. Obviously, not every bill can or should make policy feedback its top priority. Biden’s bills have included genuinely great and worthwhile stuff! But if you want to get re-elected and keep passing great and worthwhile stuff, you have to keep your eye on that particular ball.

Inflation Only Just Stopped Wrecking Americans’ Purchasing Power

So Biden and the Democrats didn’t do a good job cultivating policy feedback. But they’ve clearly done a good job shepherding the economy overall. And good economic times usually translate into approval for the president’s party. Why not this time?

Here, I’m going to repeat some points already made by folks like David Dayen. But I think the differences between Trump’s situation and Biden’s are fairly obvious, and lie in what happened in the run-up to their respective economies.

Trump had the good fortune to inherit an economy that had been on one steady, upward climb since the Great Recession. Inflation was low, unemployment was falling to levels unseen in decades, and wage growth adjusted for inflation was mostly positive. Despite his numerous and grotesque flaws, Trump did at least manage to not fuck any of that up. Biden, on the other hand, inherited an economy that had just been crushed by a global pandemic. We had a massive collapse in, and then a reshuffling of, the labor supply; we had a massive shift in demand from services to goods; global supply chains were shut down, supercharged, snarled, and thrown into chaos.

The federal government spent a massive amount on COVID-19 aid packages. Plenty of centrist, mainstream economists scolded the Democrats for their part of that spending, asserting it was overkill. But the end result was a borderline-miraculous rebound from the recession induced by the pandemic. As you can see in the graph below, the post-2020 jobs recovery (the red line) happened faster than any recession since 1981 (the lines in shades of blue). And while recoveries between 1945 and 1981 (the grey lines) happened faster, they never started from a jobs hole anywhere near as deep.

If this is Bidenomics, then in a just world, everyone would agree it’s a successful model to build upon. But we also got two years of the highest inflation we’ve seen in decades. Prices only just recently returned to a growth rate that’s sort of close to normal. So Bidenomics’ critics did a victory lap.

Long story short, the several years that preceded Biden’s current very good economic moment were a complete fucking mess, in ways not at all comparable to Trump’s economy. And that mess left us with a lot of damage that we’re still unwinding.

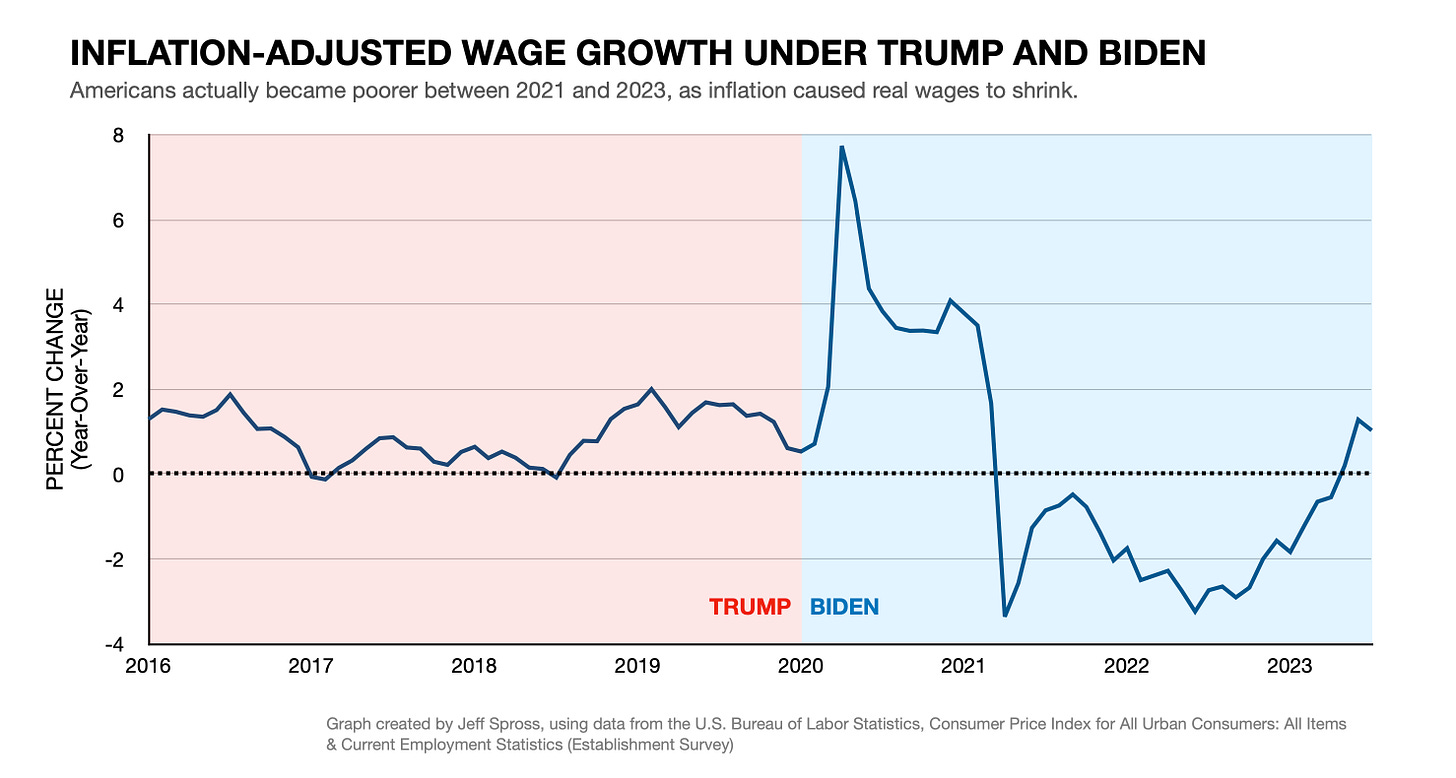

There are various ways to encapsulate or illustrate that reality with data. But I think the most straightforward is to look at the rate of real wage growth starting under Trump. (In other words, how fast have wages grown—or shrunk—once you account for inflation.)

As you can see, real wage growth each month wasn’t exactly spectacular under Trump. But it was positive a fair portion of the time. (It stayed above the dotted line.) And it never really turned negative.

Then, under Biden, everything went crazy. First, there was a big dramatic spike of positive real wage growth, followed by a negative spike. These were largely statistical artifacts: a whole lot of workers, disproportionately low-wage, left the economy and then re-entered it, causing the measured average of Americans’ wages to first jump and then drop. But by the latter half of 2021, this process had played itself out. What followed was a roughly two-year stretch where prices rose faster than wages, so people’s buying power in real terms fell. Every month real wage growth was negative, Americans were becoming poorer in terms of the concrete goods and services their incomes could actually buy.

Compared to the last few decades, this was a pretty serious bout of falling real wages, both in terms of how negative they got, and how long they stayed negative. Trump never had to deal with anything like that.

Now, the good news is that inflation has slowed down significantly while wages are still going strong. So real wage growth has turned positive again, as you can see above. But this literally just happened a few months ago. Furthermore, slower inflation doesn’t mean prices are falling, it just means they’re rising less fast. Prices throughout the economy are still really damn high. We’re going to need real wage growth to stay positive for a while before the pain of the recent inflationary bout recedes, and for people to feel like their incomes are ahead of prices the way they were before inflation shot up.

Other Tidbits Distinguishing Biden’s Economy From Trump’s

On top of being too short to generate much policy feedback with voters, the expiration of pandemic-era protections left a lot of Americans without support in an economy that was, in many ways, still recovering from an enormous shock. After falling for at least a decade, the national homelessness rate started ticking back up in 2019 and continued to rise through 2022. Compared to the pre-pandemic average under Trump, evictions are up significantly in pretty much every city and state they’re studied. Measures of food insecurity and financial distress are also higher compared to early 2020, when Trump’s economy was peaking just before COVID-19.

I wouldn’t say these numbers justify wildly broad headlines like “Bidenomics isn’t working for working people.” But they do provide additional, plausible, concrete reasons why Americans would rank Biden’s economic performance worse than Trump’s.

Dayen also points a finger at higher interest rates. I’m a bit more skeptical, because debt burdens as a percentage of household income remain unusually low—a fact we can thank the massive amounts of COVID-19 aid for. And while the Fed’s current interest rate target of roughly five percent ain’t nothing, it’s also not that high, historically speaking.

On the other hand, the Federal Reserve’s interest rate target has been at zero for most of the last 13 years. If particular economic conditions last long enough, Americans tend to adjust their expectations to fit the new baseline. A five-percent target for interest rates probably feels a lot more painful today than it did, say, back in the late 1990s. And this latest increase also happened fast. So I wouldn’t rule out interest rates as a reason for Americans’ grumpy mood, either.

Finally, to complicate things a bit further, there’s an interesting debate going on about how exactly to understand the real wage growth numbers.

Some progressives have actually been quite excited. They point out that real wage growth for the poorest third of Americans basically stayed positive roughly the whole time. The combination of pandemic labor market disruption and full employment due to government spending actually drove wage growth for low-income workers way up, and well ahead of inflation. Yet this also makes Biden’s poor polling results on the economy somewhat odd. (I think a possible answer could be that polling tends to oversample upper-class Americans, whose real incomes got hit much harder according to this analysis.)

But another argument emphasizes that incomes for low-income Americans are, well, low. And they typically spend more than they earn, with the difference made up by borrowing and government aid. So even if poorer Americans saw a big percentage gain in their wages, and a smaller percentage increase in their costs, they could still have been left worse off in dollar terms. A big percentage change in a smaller baseline number (income) can still come in behind a smaller percentage change in a bigger baseline number (costs). If you buy this take, then Biden’s poor polling results make a lot more straightforward sense.

Given that we’re talking about how to slice multiple different datasets, it’s a difficult debate to square. And I don’t have the room to referee it here.

I’m also not sure it matters for our purposes. Regardless of who’s right, we wind up in the same place: we need inflation to come down (which is happening) while we need wage growth to stay high (which is also happening). The question is simply how hard inflation hit different economic classes of Americans, and how long real wage growth needs to stay positive to repair the damage.

Biden and the Democrats Picked the Right Risk

Given how much damage inflation did to Biden and the Democrats’ political prospects, it’s worth asking: Could they have avoided inflation while still engineering a recovery as fast and comprehensive as the one we got?

In theory, I think, yes. But first, you’d have to answer the question of whether inflation was primarily caused by government spending, or primarily driven by the massive disruption that COVID-19 delivered to global supply chains. I think the weight of evidence favors the supply-side story. In which case there wasn’t much to be done except help Americans as much as we could, while we all gritted our teeth and got through the price spike. But even if you do think government spending played a much bigger role, I doubt we could’ve kept the job recovery and avoided inflation by simply spending a bit less or spending differently.

Fundamentally, I just don’t think we have good tools for dealing with inflation. There’s a world in which we do, because the ideas behind western macroeconomic policymaking—and, more importantly, the design of the institutions that deploy that macroeconomic policy—evolved in a very different direction after World War II. But that’s another newsletter entirely. We live in the world we live in, with the tools we’ve got. And the lesson Biden and the Democrats took from the Obama years was that the risks of doing too little in a recession vastly outweigh the risks of doing too much.

I think they were clearly correct in that judgment. I’m taken by Alex Williams’ metaphor of the “Dukes of Hazzard landing.” When you’re trying to jump a ravine in a 1969 Dodge Charger, you want to gun the engine both before and after you’re airborne. The last thing you want to do at any point is hit the brakes. There’s no way the landing is ever going to be pretty. But the only way to avoid disaster, and to keep any control of the car at all, is to keep your foot on the gas once you’ve hit the ground.

So while I don’t think there’s any great mystery as to why Biden is currently getting much worse marks on the economy than Trump, I also think the data we’re getting suggests that Democrats more or less pulled off the Dukes of Hazzard landing.

Certainly, some things could still go wrong. The Fed could decide they really want inflation back down to two percent right now, despite the weakening labor market, and keep increasing interest rates. And Republicans will probably shut the government down again when the next federal budget fight arrives in September. Which could do a little damage to the economy or a lot.

But barring an outside intervention of that sort, there’s no inherent reason why the economy’s current trends shouldn’t continue through November of 2024, or why wage growth wouldn’t remain positive for the vast majority of the country. So the longer real wage growth stays positive, the more the damage and pain left by inflation should recede. And the more Biden and the Democrats’ economic approval should increase.

So fingers crossed that the economy keeps healing. Because if Biden does eventually reap the political benefits of a good economy, he’ll certainly deserve it.

Unfortunately, Biden chose not to follow Trump’s example in loudly taking credit for the direct checks he sent—a bizarre choice that sort of encapsulates Democrats’ weird, reluctant flat-footedness on this subject.