The Debt Ceiling: Here Be (Stupid) Dragons

A general rundown of the whole debt ceiling mess, and why it seems to make our politicians and policymakers crazy.

Welcome to my newsletter: The Workbench! Rather than indulge in the navel-gazing of writing an actual “inaugural newsletter” with a mission statement and such—which would probably end in me never publishing at all—I figured I’d just jump right in. If Indiana Jones didn’t need an origin story, I certainly don’t either.

If you know my previous work, I’ll be covering a lot of economics; plus other issues, politics, philosophy, movies, and really whatever strikes my fancy. It’s my newsletter! The current plan is at least two installments a week.

I fear I have neither the time nor the constitution to run a comments section. But you can find me on Twitter at @jeffspross, where I may or may not have replies enabled. And you can always email me at theworkbench.newsletter@gmail.com.

The Workbench is currently free. I’m planning on a paid version, which I’ll sort out in the coming weeks. But for now, if you’re interested, please subscribe!

For the upteenth time in my adult life, America is headed for a debt ceiling crisis.

The U.S. federal government borrows by selling U.S. Treasury securities — i.e. bonds and such. And the debt ceiling is a statutory limit, passed by Congress, on the total face value of the bonds the government can sell.

Since the federal government pretty much always runs a deficit—a shortfall between how much it spends and how much it taxes in a given time period—it keeps adding to its total load of debt, and thus keeps bumping into the debt ceiling. Congress has always reached deals to raise it. But should it ever fail to, then presumably federal spending would immediately have to drop until it’s even with tax revenue, so all borrowing can stop. That would mean gigantic cuts to all sorts of federal programs, and quite possibly a default on the debt the U.S. government already owes.

We technically reached the current limit of $31.4 trillion on January 19. But the U.S. Treasury Department has some tricks—referred to as “extraordinary measures,” in policy-speak—to keep federal spending going for a few months without technically borrowing more. Those will last us until sometime in June, which will be the real “drop dead” date for a deal.

Since we’re currently in the shit, and since I imagine this is far from the last debt ceiling fight we’ll see, I figured an overall “table-setting” newsletter on the issue was in order.

The most fundamental thing to remember about the debt ceiling is that it’s a case of the U.S. Congress flagrantly contradicting itself. Whatever else you make of the issue, the bedrock fact driving the whole mess is that Congress has passed laws saying irreconcilable things.

The Treasury Department and the other agencies of the U.S. government do not spend a single solitary cent without Congress’ authorization. They do not collect one single cent in taxes or other revenues without Congress’ authorization. And when federal spending exceeds revenues, other laws passed by Congress say the Treasury Department cannot just print money to make up the gap; they have to borrow.

But with the debt ceiling, Congress has also created an arbitrary limit on the total number of U.S. Treasury bonds the federal government can sell. So we’re always running the risk that the spending and taxation combo Congress has authorized will require a level of borrowing that Congress has not permitted. Legal scholars Neil Buchanan and Michael Dorf call the collision of these three laws the “trilemma.” And assuming we actually hit the debt ceiling, it will place the U.S. President in an impossible bind: “He can, at most, faithfully execute two of the three laws in question, but not all three,” as they put it.

This constitutional and economic crises-in-waiting also creates an opportunity for particularly ruthless politicians: Policies that would never pass the legislature on a normal up or down vote can be demanded as the price for enough votes to raise the debt ceiling and avoid catastrophe. Fights over the debt ceiling become a way for politicians to have their cake and eat it too—to cancel the decisions of previous Congresses, without having to muster the votes to pass an actual, specific repudiation of those laws. And in recent decades, Republicans have become particularly enthusiastic about exploiting this bit of leverage.1

Democrats currently hold the White House and the Senate. But the GOP recently won the slimmest of slim majorities in the House of Representatives. And apparently House Speaker Kevin McCarthy had to concede to another debt ceiling fight to get certain GOP factions to back his speakership. Then we hit the debt ceiling shortly after, and here we are.

The most obvious solution to this ongoing cycle of stupid crises is to simply get rid of the debt ceiling entirely. But plenty of people in both parties—including President Biden himself, apparently—oppose that option. The general thinking seems to be that the debt ceiling helps maintain fiscal discipline. Bracketing aside the question of whether our ever-increasing debt load is a genuine problem (it’s not), the “fiscal discipline” argument ignores the blunt fact that if Congress wanted to spend less money or raise more tax revenue, it could simply pass less spending or raise taxes. There’s no need for this bizarre two-step. You might as well rack up a big credit card debt, then refuse to pay the bill, and call that “fiscal discipline.”

Meanwhile, various proposals to get around the debt ceiling, should Congress fail to raise it, have prompted accusations of caesarism: that doing an end-run around the debt ceiling would violate America’s constitutional balance between Congress and the Presidency, aggregating even more unaccountable power to the latter. Which again ignores that all the various bits of spending legislation that pushed us past the debt limit are the laws of the land as much as the debt limit itself.

If the executive branch ignores the debt ceiling, yes, it will be disobeying Congress. But if we hit the debt ceiling, and federal agencies just stop doing the spending authorized by Congress—from Social Security benefits to wages for federal employees and everything else—they will also be disobeying laws passed by Congress. They’ll just be disobeying different ones. In either case, you get a breach of the Constitution’s separation of powers.

The U.S. government deficit spends by roughly 12 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) at the moment. Thus, obeying the debt ceiling would require an immediate cut to federal spending equivalent to 12 percent of GDP. That is an absolutely massive reduction. For comparison, the Great Recession reduced GDP by around 9.5 percent before the economy started growing again. And that was while federal spending was going up and the federal deficit was increasing—as tax revenues fell and automatic welfare programs kicked in and the 2009 stimulus took effect—countering the drag from the collapse in employment and investment.

Then there’s the multiplier effect: every dollar the U.S. government spends helps to employ someone in the private sector, which leads to a further consumption increase, and so on. Meaning every dollar of federal spending actually tends to increase GDP by a dollar plus some more. And the reverse holds true for reductions in government spending. So if we cut federal spending by 12 percent of GDP, the actual fall in GDP would likely be larger. Probably around 18 percent, and perhaps even more.

In other words, if we just leave the debt ceiling as is, and cut spending in June to obey it, we’ll be in for something worse—quite possibly much worse—than the Great Recession of 2008.

Another issue is that U.S. Treasury bonds are a benchmark safe asset around the world. Every portfolio and financial trade, from the most humble retiree’s investment strategy to the biggest and most complex transaction Wall Street can dream up, relies on the assumption that U.S. Treasuries are a safe hedge—the gold standard for risk-free investment. That’s because the U.S. federal government, like House Lannister, always pays its debts.

But the shortfall between federal spending and tax revenue includes payments on the debt the U.S. has already taken on. So if we cut enough spending to abide by the debt ceiling, the U.S. could default on debts it already owes. Theoretically, we could avoid doing that; but only by cutting deeper into other programs, wreaking further havoc in the real economy.

What happens if we do default on debt payments? Well, no one really knows. Presumably investors and institutions around the world would start dropping U.S. Treasury bonds from their portfolios, maybe to a modest extent, maybe to a huge extent. But the Federal Reserve could always step in to buy those bonds and keep interest rates on an even keel. Frankly, it is extremely unusual for chaos in financial markets to impact the real-world drivers of economic health: investment and employment. The causal arrow generally runs in the other direction—it’s the spending cuts that result from a debt ceiling breach that would really destroy investment and employment, and thus tank the financial markets. A more likely problem is the U.S. Treasury sell-off would also drive down the value of the U.S. dollar relative to other currencies, making our imports more expensive and driving up inflation. So we’re talking about a potential inflationary shock on top of a sudden change to U.S. fiscal policy that’s already pretty much guaranteed to set off a recession bigger than what we saw in 2008.

But no matter how you slice it, it’s not a good mix, which is why the debt ceiling creates such a potent opportunity for hostage-taking. Politicians can effectively put a gun to the head of the U.S. economy, then threaten to pull the trigger (by refusing to vote for a debt ceiling increase) unless we give them whatever policy concessions they demand—which they of course couldn’t pass under normal circumstances, otherwise, why tie them to the debt ceiling?2

Which is precisely why the Biden White House and the Congressional Democrats shouldn’t do a deal. This is completely unsustainable. Not only is it the economic equivalent of juggling a live hand grenade, it’s a complete perversion of the way legitimate decision-making in a representative democracy occurs. A legislator might as well walk onto the House floor wearing a suicide bomber vest, and threaten to set it off if their colleagues don’t vote for the policies they want. To their credit, Democrats seem to understand that this time, and are refusing to negotiate over a debt ceiling increase.

But the problem with games of chicken is that it’s never actually guaranteed that the other guy’s nerves will fail first, even if they’ve repeatedly failed in the past. Patterns continue until they don’t. So let’s say no one’s nerves fail, the cars actually crash, we don’t get a Congressional deal, and we reach the drop-dead date in June. That kicks matters over to the executive branch, since its the Treasury Department and other agencies that actually carry out the fiscal policies Congress has authorized.

Other than obeying the debt ceiling, what are the executive branch’s possible options? There seem to be three big ones: just ignore it, mint a trillion-dollar platinum coin, or have the Treasury Department sell bonds at a premium.

Ignoring the debt ceiling, and carrying on borrowing and spending as if nothing has happened, is what Buchanan and Dorf actually advise doing, on the grounds that it’s the “least unconstitutional” option. People sometimes point to a clause of the 14th Amendment that arguably renders the very existence of the debt ceiling unconstitutional, but Buchanan and Dorf’s point is that you don’t even need to get that detailed; simple respect for the separation of powers will suffice. Because, if the executive branch disobeys the debt ceiling, that’s all it disobeys. But if it obeys the debt ceiling, that leaves a pot of money far too small to carry out all the programs Congress has authorized. And at that point, the Treasury Secretary and her department will have to just unilaterally decide which programs will still get funding, and how much—i.e. they’ll be picking and choosing which laws to disobey among all the spending laws Congress ever passed. Because what else can they do? Congress has told them not to sell any more bonds, but it hasn’t told them how to apportion the resulting cuts. So obeying the debt ceiling results in a much worse “power grab” by the executive branch than disobeying it.

Next is the trillion-dollar coin option. If you’re on Twitter (God help you) or in the weeds on this stuff, you’ve probably heard of this. Physical coins and cash are produced by the U.S. Mint, which is part of the Treasury Department. As I said earlier, the law forbids the Treasury Department from just minting U.S. dollars to pay for federal spending. But it turns out Congress unwittingly created a loophole in that rule, with legislation that allows the Treasury Secretary to mint, at their discretion, a platinum coin of any denomination they wish. So the idea is, we hit the debt ceiling, the Treasury Secretary orders the U.S. Mint to make the trillion-dollar platinum coin, then it’s deposited in the Treasury Department’s account at the Fed. And poof, the Treasury Department has one trillion dollars in its account to continue spending with, no further borrowing needed.

Rohan Grey has a paper arguing that minting the coin itself is fully within the Treasury Department’s authority as delegated by Congress. And since it allows the executive branch to continue obeying Congress’ spending decisions, as well as Congress’ orders to not borrow any further, this option is actually on firmer constitutional footing because it provides an escape from the “trilemma.” Buchanan and Dorf disagree, based on how they interpret the debt ceiling statute, and their doubt that the Supreme Court would actually allow the relevant platinum coin law to be used for such an inventive purpose. I find Grey’s position more persuasive, but I’m hardly an expert.

Of course, the Biden administration could presumably be sued for following Buchanan and Dorf’s advice as well. And in both cases, the White House would find itself before a very unsympathetic Supreme Court with a rightwing supermajority. On the flip side, and again in both cases, it’s hard to see who could sue the Biden administration in the first place, outside of members of Congress themselves. To bring a suit, you have to have standing—i.e. you have to show the executive branch’s decision harmed you in some way—and the whole point of both these gambits is to prevent harm to the rest of American society.

As for selling bonds at a premium—the latest option to enter the discourse—here’s how that would work: A Treasury bond has a face value, and it has an interest rate it pays, but the amount of money the bond actually sells for is a function of both. So the Treasury Department could get considerably higher than the face value of the bonds it sells, if it offers a really high interest rate. It’s called selling at a premium, which happens all the time in financial markets. And crucially, the debt ceiling only limits the total face value of bonds the Treasury Department can sell. There’s no restriction on how much interest the Treasury Department can pay, or how much it can get for those bonds.

So the Treasury Department could use whatever money it still has in its accounts to start paying off existing bonds it owes, then it could sell new bonds for the exact same face value, but offer much higher interest rates. This would swap out bonds of equivalent face value, so it wouldn’t increase total face-value debt and thus breach the debt ceiling. But it would also get more money into the Treasury Department's account than it had before, allowing it to keep federal fiscal operations going longer.

The power to sell bonds with any kind of interest rate structure it prefers sits well within the Treasury Department’s powers, so it’s hard to see how any plausible constitutional challenge could be raised. Along with just ignoring the debt ceiling, this approach only requires the cooperation of the Treasury Department, whereas minting the trillion-dollar coin requires the cooperation of the Federal Reserve as well.3 On the other hand, ignoring the debt ceiling is a one-and-done solution, and presumably you’d only have to mint a trillion-dollar coin once or twice, whereas selling bonds at a premium is something you’d have to keep doing iteratively as long as the crisis lasts—presumably with ever-higher interest rates.

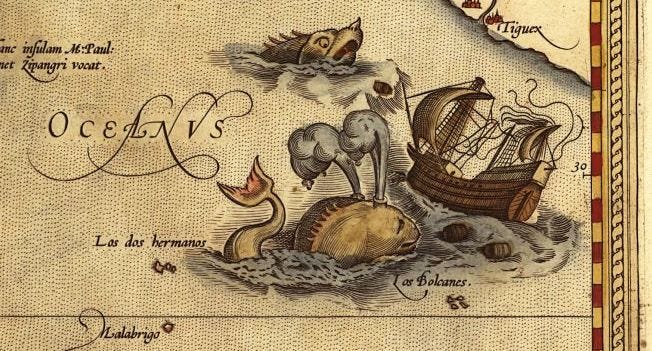

I’m honestly not sure which is the “best” route. But I’m less interested here in parsing the particulars of the executive branch options than in what the reactions to those options tells us about American governance. This debate crosses over into the “here be dragons” part of the constitutional map, and that tends to reveal people’s unspoken assumptions about what’s “really” important and how the world “really” works.

For instance, President Biden didn’t say it would be irresponsible to ignore the debt ceiling; he said it would be irresponsible to not have one. He thinks we should keep the trilemma in place! It’s hard to believe he’s actually thought through the governance consequences of that position. Rather, many American leaders in both parties seem afflicted by a bone-deep religious conviction that the country spends too much; and that any outcome that reduces the debt is just inherently more legitimate, even if getting to it risks political and economic upheaval. As Buchanan and Dorf point out, no one ever contemplates having the executive branch just unilaterally raise taxes, even though that would be no more unconstitutional than unilaterally cutting spending. The unspoken instinct here seems to be that the debt ceiling creates an unfortunate-but-necessary backstop to force the country to adopt certain fiscal policies that the normal, legitimate democratic process isn’t willing to adopt on its own.

In his paper, Grey observes that the trillion-dollar coin option also breaks people’s brains in particularly strange ways. Beyond Buchanan and Dorf’s legal reasons for rejecting the coin option, they also have some strange worries about mass social psychology. Buchanan and Dorf are themselves perfectly aware that money is a social construct: mere pieces of paper and digital bytes, imbued with meaning (or “backed,” in the common parlance) by nothing more than our collective trust in one another. They know the U.S. government can create as many U.S. dollars as it wants, just like a scorekeeper in a baseball game can “create” as many points as they want. But Buchanan also seems to think this is a kind of gnostic wisdom, properly known only to the elect: “If people understand that money is a social contrivance but continue to go along with the group delusion (as I do), great. When too many refuse to go along, however, we are all in danger,” he writes. “People on high-wires should not look down, and the experts should not tell them to do so.” And in his estimate, minting the trillion-dollar coin would be a very dramatic way to encourage everyone to glance past their feet.

Setting aside the blatant elitism of this position—that most Americans couldn’t handle knowing the true nature of money without rioting in the streets or crashing the markets or recreating the pilot episode of The Last of Us or something— it’s worth considering that Buchanan and Dorf get the causal arrow backwards: It’s not that the economic system works because everyone participates in the “group delusion” that money has value. It’s that everyone participates in the “group delusion” because the economic system works. And if that’s the case, then any disruptions caused by the spectacle of ignoring the debt ceiling or minting the trillion-dollar coin pale in comparison to the concrete effects of actually obeying the debt ceiling and cutting spending.

There’s a weird tendency in these debates to assume that ideas and cultural abstractions are what drive material conditions on the ground, rather than the far likelier and less mystical possibility that it’s the other way around. Perhaps Americans can understand the true nature of money just fine; perhaps they probably already do, if pressed for a moment. And, after watching the spectacle of the trillion-dollar coin go down, perhaps they would simply carry on with their economic lives as before, but now with a slightly better understanding of the true shape and limits of the U.S. government’s fiscal capacities.

One last oddity is how all the major players—President Biden, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell—keep insisting that all the executive branch options are nonstarters, and only Congress can solve the debt ceiling crisis.4 On the one hand, I get David Dayen’s argument that they have to say this, because if they admitted otherwise, then any chance of the Republicans surrendering goes out the window. You don’t admit the executive branch options are actually options until you absolutely have to. (Whatever anyone says for strategic or optical purposes, it’s hard to imagine either a Treasury Secretary or a Federal Reserve Chair refusing any of these schemes if the country’s back was really against the wall.)

On the other hand, do we actually need the Republicans to surrender? The debt ceiling is a unique clusterfuck because it makes it impossible to keep running fiscal policy according to Congress’ previous compromises, even if a new compromise cannot be reached. I agree it’s a shame if new compromises can’t be reached. But Biden is right that reaching a new compromise is and should be a separate issue from fulfilling the fiscal operations that successful Congressional compromises have already committed the federal government to.

If we breach the debt ceiling, some hit to the confidence voters and financial markets put in the governance of the United States is already built in. You hear a lot of worries about “spooking the markets” with the executive branch-only solutions. But as I said above, financial markets get spooked all the time without the damage bleeding into the real economy. It’s possible this time could be different. But what’s certain is the severe damage we’d do to millions of Americans’ concrete well-being if we go ahead and cut all that spending.

If Biden and Yellen just announce now that they’re going to ignore the debt ceiling or mint the coin and sell bonds at a premium or whatever, then yes, Republicans will totally refuse to budge on the debt ceiling. But then the debt ceiling won’t matter anyway, so why do we care? Meanwhile, debates over future budgets and appropriations will proceed as they always have, for good or ill. So the fact that Democratic Party leadership is united in a desire to back the GOP into a corner feels like an instance “politico brain” to me—forgetting that what actually matters is not the spectacle of humiliating your opponents in the legislature, but what material policy consequences you create for the American people.

Having Congress eliminate the debt ceiling entirely is the ideal solution: This is fundamentally a political problem, created by Congress, and the “cleanest” fix is for Congress to uncreate it. But they may well not. And if the first-best option is for Congress to scuttle the debt ceiling, it’s hard to deny that the second-best option is for the executive branch to just unilaterally neuter it.

For a long time after the country’s founding, Congress borrowed on a piecemeal basis, authorizing the sale of new Treasury securities to meet the financing needs of each spending bill as they passed, and often detailing the makeup of those securities—maturation dates, interest rates, etc—in great detail. By the time World War I hit, this hands-on process had become too cumbersome. So Congress largely automated things, giving the Treasury Department greater leeway to sell whatever design of securities it saw fit, while setting an overall limit on the total face-value of Treasury securities that could be sold. Since then, the direction of change has been towards even more freedom for the Treasury Department to structure debt as it wishes, as long as it stays under the overall debt ceiling limit. Ironically, the debt limit began its life as an attempt by Congress to give the Treasury Department more freedom in determining fiscal policy, not less. At any rate, conflicts set off by the “trilemma” have waxed and waned since then. They heated up in the 1980s, and then really got cooking during the Obama administration, as polarization in Congress increased and Republicans demanded major spending cuts in exchange for a debt ceiling increase.

You could imagine a batch of cantankerous lefty politicians refusing to raise the debt ceiling unless we pass Medicare-for-All or something. But in practice, the debt ceiling has always been taken hostage by people who want to cut spending. I suppose that’s because there’s a thematic resonance between cutting spending and refusing to borrow more. But mostly I bet it’s just that people indifferent to the suffering that would be caused by spending cuts are also indifferent to the suffering that would be caused by crashing into the debt ceiling.

In one sense, the Treasury Department’s relationship to the Federal Reserve is just like your relationship with your bank. The Treasury Department has an account at the Fed, which gets filled by federal revenues from taxes and borrowing, and emptied by federal spending. So if we minted the trillion-dollar coin, the Fed would have to agree to take it as a deposit. The difference, of course, is that your bank is a separate for-profit entity that doesn’t give a shit about you, and will only accept unusual deposits from you if it’s convenient for their bottom line. But the Federal Reserve is part of the federal government, created by Congress, and it’s legally obligated to care very deeply about the U.S. government’s fiscal stability.

When asked about the options for the executive branch to unilaterally deal with the debt ceiling, officials and spokespersons for the Biden White House have repeatedly said Congress raising the limit is the only workable option. “I believe the only way to handle the debt ceiling is for Congress to raise it,” is how Yellen put it. She’s also rejected the idea of picking and choosing which fiscal obligations to honor. And she’s called minting the trillion-dollar coin a “gimmick,” pointing out that the Fed isn’t required to accept the coin. Notably, she never said the Fed wouldn’t accept it; just that it’s up to them to do so. (And they arguably are required to accept it.) As for Fed Chair Powell, he’s said that “there’s only one way forward here, and that is for Congress to raise the debt ceiling” and that “any deviations from that path would be highly risky.”